I’ve been taking

a break. It wasn’t planned. It just happened. In fact, I hardly realized it was

happening. I just suddenly awoke to the fact that it was about to be August, and

when I looked up at the wall calendar over my desk, it was showing May.

“What the hell?” I thought. Did two months really get completely away from me? It was then too that I realized that I had written nothing for this blog in five months. I mean, it wasn’t as if I didn’t know I hadn’t written anything “in a while”. But five months!

I changed my

calendar and promised myself to get it together, to return to my usually highly

disciplined writing schedule, to shrug off apathy and start living again.

Then, all of the

sudden one morning, I glanced at the date on my laptop, saw it was September,

raised my eyes to look at the calendar on my wall, and saw that, there, it was

still August. What the hell! Yet another month had drifted past. I was

beginning to feel a little like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day, but

without the state of immortality or all of the quaint and interesting

townspeople.

The fact is,

however, that I haven’t just been “vegging out” for more than five months. I

mean, I’ve been working. A lot. Until two months ago, I was still at least

keeping up my literary blog, The Southern Yankee. But I had also gotten

impossibly behind on a ghost-writing project.

I was contracted

more than a year ago to ghost the autobiography of one of the lesser-known members

of one of America’s traditional “royal families”. You would all know the name.

Just about everyone in the Western world would. When I was first approached by

the publisher for this private edition book and asked to provide a deadline, I

said I figured three months give or take.

By the time

we’re through, it will be more like a year and three months. It’s become

impossibly unprofitable for me, even though I managed to talk the publisher

into negotiating a fifty percent increase in my fee. The publisher can’t wait

to be done with it either. And like me, they claim, they’re losing their shirt.

But at least

they have the advantage of owning a book that, although it is likely to have a

very limited audience, that audience is filled with people who might very well

entrust them with their own life stories, especially because this promises to

be a good book. Myself, I don’t have that advantage. When I’m done, I’ll

breathe a sigh of relief that a difficult project is finished and pat myself on

the back for a job well done. Or then again, maybe I’ll just think bitterly

about how much time and energy I put into a book that isn’t mine in any real sense—thousands

of hours of time and energy when time and energy are at a premium in this

chapter of my own life—for a book that no one will ever know I wrote. Hence the

term ghostwriter.

There was a time

not all that long ago when, once I’d given my word, I would have met that

deadline even if it nearly killed me. And I would have met it by doing “the

best I could” in the time allotted. But there’s something about reaching this

stage in life (seventy plus, with a forty-seven-year writing career behind me) that

makes you immune to a lot of the rules you once imposed on yourself—or let others

impose on you. Priorities change when you are no longer “building a career for

yourself”, when your reputation is already well established, and, furthermore,

when you know that the time has come for your career, such as it is, to be

whatever you want or don’t want to make of it.

It didn’t take

long to figure out that I was way off on my estimate. Especially when I had

written the first two chapters which contained a great deal about the

world-famous family to which the subject belonged, only to have her reject them

out of hand. This was her story, she said, not that of the family to which she

had often wished she didn’t belong, because it was more of a burden than a

benefit.

So, there was a

rather lengthy process of making her understand that while her life might be

interesting in itself to a handful of friends and family members, what made it

more interesting to a much broader audience was that she was a relatively

unknown member of a very well-known family and that even though she

might want to be her own person, it was impossible to separate how her life had

been from the fact that she came from a very wealthy and very famous clan. The

truth was, just about everything that had happened to her was inextricably

connected to that fact. There was simply no denying the fact that being who she

was born had a profound effect on her being who she had become.

More

specifically, what was perhaps most interesting of all was that the story was

her personal history within the environment created by that family. Indeed, how

she had coped with that—and how different her life had been from what an

outsider was likely to imagine—was the main value of telling her story.

Renegotiating

the storyline and the telling of it with her took several months. Then

suddenly, one fine morning, she got out of bed on the other side, and it was

all systems go. The pause, however, gave me time to think as well, and I

decided that I was no longer okay with publishers imposing impossible deadlines

on me or setting any but the most basic of rules for how a story would be told.

I no longer wanted to feel like I was digging ditches instead of writing,

obliged to write for money rather than getting paid for writing the very best

way I knew how.

It was a kind of revelation. I discovered that I was no longer capable of writing any way but my best. Not the best that time or publishing constraints allowed, but as well and as authentically as I knew how. As a result, the narrative that I am now very close to finishing for the client—and in which I will have no acknowledgement whatsoever, since that is the fate of the ghost, a job that couldn’t be better named—is of far higher quality and authenticity than could ever be expected for a private edition, such as this will be..

What’s important

about this isn’t that I’ve gone above and beyond for the client—which I

have—but that I have been true to myself and my craft. I haven’t compromised on

research, fact-checking or quality writing, and that achievement is of major

importance to me as a writer. What it has meant is that an assignment that

could have turned into a nightmare has instead made me feel accomplished—not

like a hack to whom the importance of the money far outweighs the importance of

the work.

But I can’t

blame free-lance work entirely for being as remiss as I’ve been in fulfilling

my commitment to my regular readers, or in at least letting them know earlier

what was going on.

Regarding this

point, I can only say that there were just entirely too many external factors

eating at me to permit me to concentrate on more than one creative task at a

time. In short, my normally robust multi-tasking mechanism was jammed by

extenuating circumstances. My growing concern over these external factors

seemed to cut me off at the knees, to partially cripple and disable my usually

ample and eclectic creativity.

To start with, in

the months since I wrote the last entry here, my sister-in-law passed away. It

shouldn’t have been unexpected. She was eighty-two and had been seriously ill

for three years—what doctors described as dementia accompanied by Parkinsonism.

We, the family, had been supervising her care for that entire time. And we

decided early on that we weren’t going to have her placed in “a facility” since

she had been single and independent her entire life and had lived in the same

century-old apartment on a busy avenue in Buenos Aires for the past three and a

half decades. She would, we decided, end her life surrounded by the things she

was familiar with.

Twenty-four/seven,

she was in the capable hands of a male nurse, who was a friend of my

brother-in-law’s, and his sister, who took turns seeing to her many, many needs.

Thanks to their effectiveness and care, she didn’t spend a single day in the

hospital and they became so attached to her that they considered her a sort of

surrogate grandmother—and cared for her more and far better than the majority

of young people would care for their real grandmother. Their loyalty to her was

absolute.

On several occasions,

the work and knowhow of the nurse pulled her out of downward spirals that

should have ended her life. And the next day he would again have her sitting at

the table for her meals and doing supervised exercises in her bedroom or in the

patio, depending on the weather. We had long since understood that this wasn’t

like some other terminal illnesses that have a more or less accurate prognosis.

We simply were in it for the duration, as she would have been for any of us. So

there came a time when we had almost forgotten, as one does, that death would

be the ultimate factor.

So, it came as a

sort of vaguely anticipated shock when the nurse called to say that, after

having her breakfast like any other day, her blood pressure started dropping

steadily. He got her on a drip and sought to bring her back the way he had

before, but this time she simply went to sleep and slipped away. It was over

and the feeling was one of utter emptiness.

Like a lot of

other people, I had already become saturated, frustrated, jaded with the

general climate in which we are all living—the seemingly endless pandemic and

the great divide between science and politics that is perpetuating it; the

juxtaposition of democracy and authoritarianism that is no longer the worldwide

phenomenon that used to geopolitically divide East from West and North from

South, but which now is threatening to end the once largely successful two and

a half-century-old experiment in American political tradition, and the general

sense of being utterly fed up with an atmosphere in which those who should be

representing the people are obsessed with their own selfish political goals and

no longer do anything for the good of their constituencies because they are too

busy trying to put each other out of business.

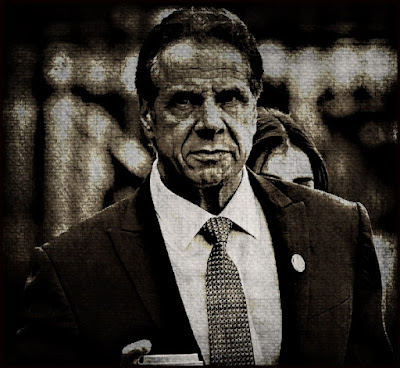

Writing last

March about the sexual improprieties of a governor I had long admired and whom

I’d hoped would one day run for president had, on top of all the rest of this,

been highly discouraging. And it seemed to mark a point of inflection in my

years of political commentary. There was a feeling that no one could be trusted

anymore to do the right thing. It seemed as if everyone had lowered their bar

to the dismal standard of ethics set by Donald Trump—as if we’d reached a point

of no return. It wasn’t that I made a conscious decision to quit writing this

blog. It was just that I could no longer seem to work up the energy to write

yet another essay about just how bad things had gotten.

Never mind that

I’ve spent an enormous amount of my career commenting on political and social

realities and am bound at some point to keep doing the same because I can’t

stop trying to analyze what often seems so utterly incomprehensible. For even

an obsessively political person like myself, however, there are moments when you

are simply fed up and can’t think about it anymore for a while without feeling

nauseous. And the current moment in politics almost everywhere, but especially

in my native United States, is a perfect one in which to feel nauseous.

But life goes

on. And giving in to despair is not only an attitude of defeat, but also a

monumental waste of time. So, I’m back, and with new impetus, and an

unwillingness to compromise my vision of the past or of the future in the

slightest, whether writing for my literary blog or for my political blog.

Because my writing is who I am, and if I can’t be completely honest with myself

and with you at this late stage in the game, when will I ever be?

No comments:

Post a Comment